Potable water supplies are best taken from upland reservoirs – which are known to have lower levels of nutrients and pollutants, making the treatment process more natural and less expensive.

Talla reservoir construction was completed in 1899 to supply Edinburgh with its potable water supply. Water is gravity fed through tunnels. The construction was done by hard labour, employing many men and powered by steam. The dam is earth-fill – and one of the largest of its kind, with an impervious core and tightly packed cobblestones protecting the face of the dam. The reservoir is supplemented by water from the Fruid reservoir, to the south, which was built in the 1960s.

Construction was completed in 1983 to supplement Edinburgh’s potable water supply, since the older reservoirs were no longer adequate to meet current and projected demand. It was built by damming a valley at a narrow point. Farms and dwellings in the valley bottom had to be moved, along with a historic ruin of Cramalt tower. The operators of the reservoir now Scottish Water had to provide new housing and have the responsibility of disposing of sewage from the dwellings and sheep-dip used on the farms. Farming and forestry activities in the catchment are monitored to ensure that there is no use of chemicals which could damage the water supply.

The dam is earthfill but with a steeper slope on the pond side than Talla. It is grouted into the bedrock which has been pressure-grouted to ensure that the fissured rock does not leak. All the control works are built in to the dam itself: It does not have a separate spillway, but the excess water spills down a gap around the draw-off tower, and is discharged into a stilling basin at the foot of the dam.

Water is discharged through the stilling pond as there is a compensation flow maintained to keep the river in a viable condition, and at the time of our visit this was supplemented by a ‘freshet’; an artificial spate to mimic normal flow variation in a river, and specifically to aid the upward migration of spawning salmon.

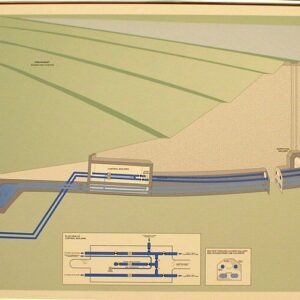

This is the view from the draw-off tower to the head of the reservoir, and from the head of the loch looking towards the dam. The catchment has an area of 40km-2, and the reservoir a surface area of 2.6km-2 and capacity of 64 million m-3. It is capable of supplying 100,000 m-3 per day.

The spillway shaft: the draw-off tower is a double cylinder, with the outer annulus forming the spillway and the inner tube containing stairway, lift, draw-off pipes and valves, a laboratory and other monitoring equipment.

Water can just be seen at the bottom of the shaft: it is being drawn off via the scour pipes at the bottom of the reservoir to form the freshet. These pipes allow water to be run to waste without drawing from the better quality water levels higher up. The tower has 5 levels at which water can be drawn into 2 separate pipes, which means that one side could be shut down for maintenance if necessary. At the bottom of the tower the vertical draw-off pipes turn to the horizontal and the flow from them into the main supply pipes is controlled by a butterfly valve. The grey cylinder is the control gear for the valve: it can be operated remotely, or electrically by hand, or manually by turning the grey wheel. The round vertical plate is an inspection cover which can be removed to allow inspection of the pipe. The blue valve on top of the pipe is an air-release valve to release trapped air when the valve is opened again. The horizontal pipe runs in parallel with the access tunnel. There is another pipe at the other side, and underneath the tunnel is the spillway channel.

The tunnel connects the bottom of the draw-off tower with the control gallery; the two draw-off pipes run alongside, with the spillway drain underneath. Inside the control gallery are the distribution pipes. The outer end of the access tunnel can be seen, with alongside them the two draw-off pipes. They are linked so that one side could be taken out of commission without affecting the way the water is distributed

The two outer pipes are the supply pipes which carry the water into the tunnel cut between Megget and the Manor Valley. Once into the Manor side, the water re-enters a pipe for delivery to Edinburgh’s water treatment system. Some parts of the pipework are duplicated where it has to pass under roads, rivers, etc. Water is distributed to Gladhouse and Glencorse reservoirs for intermediate storage, or passes directly to water treatment plants at Alnwickhill, Fairmilehead, and Marchbank as well as some smaller works which supply parts of Midlothian.